2014 Student Blog Post #2: Steven Sarich

Elemental Fingerprinting Using Portable X-Ray Fluorescence

My names is Steven Sarich and I’ve just completed my first year in the Industrial Archaeology MS program at Michigan Technological University. I began my academic career at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln graduating with a degree in anthropology with a focus on archaeology. My interests are primarily in work processes and tracing the sequence of production and discard of material culture.

For me, understanding this process means studying objects closely, delving into archival material, and listening to the oral histories of people, but also using more sophisticated archaeological science techniques that allow me to understand artifacts at the microscopic and elemental levels.

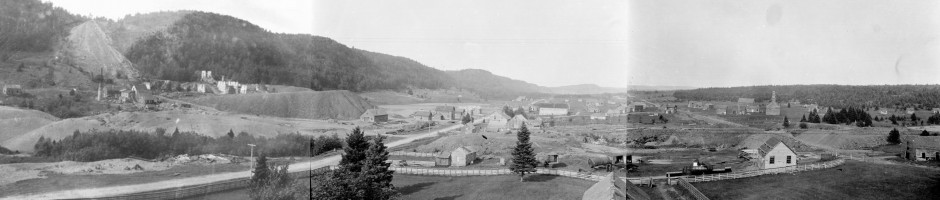

I was excited to have an opportunity to try and use elements to examine the residues of how people used space in Clifton during this field school. The tools available to the contemporary archaeologist are many and varied ranging from the simple to the highly technical, though all are employed together to facilitate a deeper and richer understanding of an archaeological site and its history. In this case, the Clifton “Interyard” in an area between a group of large frame-built buildings at the center of town. Our primary driving questions go beyond the individual artifacts recovered. For example, what can the soil itself tell us about what people did with these spaces and how do we get it to reveal its secrets? On one hand, we can read the landscape to see alterations to the ground’s surface based on our understanding of natural processes, or plunge down below its surface to view the changing stratigraphy of depositing fill to raise the ground here or digging to remove soil and effect drainage there.

This season, we found ourselves in possession of a unique opportunity thanks to Bruker Elemental (http://www.bruker.com/elemental). Bruker makes a device designed to excite materials into revealing their particular chemical composition. This device, called the Tracer III-SD, is a field portable X-Ray Fluorescence Analyzer (pXRF) which is gaining ever greater traction in the archaeological community as another useful tool for studying the archaeological record, and in particular, the context in which it is found.

We know that many of our readers have very technical education, but many do not so to get a basic understanding of how this instrument works, it is helpful to look to the atom and how it interacts with X-rays.

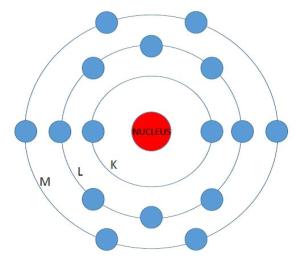

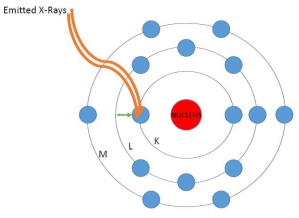

A sulfur atom, with sixteen electrons in three valence levels. This is the atom in it’s normal state.

1. This first image depicts a simple schematic of an atom which consists of a nucleus surrounded by three electron shells labeled as the inner “K” shell, the middle “L” shell, and the outer “M” shell. The electrons orbit in these shells, swirling around the protons and neutrons packed in the nucleus. A stable atom has the same number of electrons in orbit as protons in the nucleus.

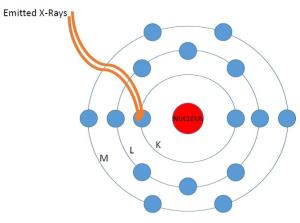

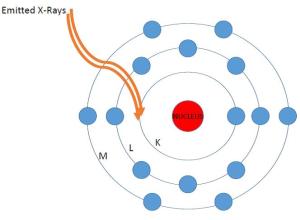

This sulfur atom is bombarded with X-rays and a few of those hit electrons at the inner K valence level.

2. A soil sample (Clifton “Interyard” soil samples in our case) is placed under the Tracer III-SD. The instrument generates X-rays that bombard the atoms in the sample. Some of the X-rays strike an inner “K” shell electron causing it to break free from the atom.

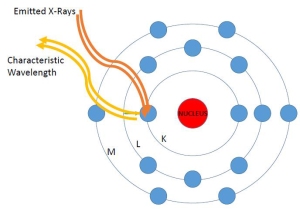

3. Because of this absence, the atom becomes unstable and seeks to regain its prior neutral state…

4. Toward that end, an electron from one of the outer shells takes the place of that absent inner shell electron, in this case an “L” shell electron is transferred into the position of the removed “K” shell electron.

5. As a result of this transfer, energy is produced in the form of characteristic electromagnetic wavelengths captured by the detector in the instrument. These wavelengths are unique to each of the elements on the periodic table. This is very roughly analogous to the way piano strings of different lengths emit sound energy at different wavelengths, thus allowing us to hear different notes. The emitted energy allows us to see the elemental composition of samples and get some sense of the concentration of those elements based on the counts of fluoresced atoms.

My job is to adjust the scale of inquiry from the atom or the single sample to map multiple samples taken across a large space such as the “Interyard” area at Clifton. From an environmental perspective, we can gain a sense of how certain relevant elements such as copper, zinc, lead, arsenic, etc. move in the soil. Because people’s actions leave residual traces in the physical world archaeologists eye these chemical maps as potential traces of activity areas, where people tended to repeatedly do similar tasks or activities. These activity areas become visible because people’s actions and their material culture (objects) interact with the surrounding context in the world and because we have mapped our work and the historic records of Clifton so intensively over the years, we can examine the chemical and artifact distribution map overtop of the topographic maps and aerial photos and historic maps and photos.

Bruker Tracer III-SD Handheld X-Ray Florescence Instrument (“pXRF”) shooting samples in the back of the Michigan Tech Van while parked on Cliff Drive. Courtesy of Bruker Elemental (http://www.bruker.com/elemental)

Studying soil chemistry patterns is nothing new in archaeology-professionals have done this for many decades. But this instrument is so very quick and fast, allowing sampling in the field and giving immediate feedback about the intensity of so many different elements, it is a very powerful tool that is making this kind of study increasingly possible to more and more scholars.

Thanks to the generous people at Bruker, we set out to attempt this research at Clifton during the 2014 field season. Over the course of one week, the soil team was able to establish a 25 x 60 meter grid at the interyard and take 67 samples at five (5) meter intervals. Because of the portability of the Tracer III instrument, a majority of the soil samples were analyzed in the field allowing us to gain a great deal of preliminary knowledge about the chemical distribution. Subsequent to the sampling, a mapping team came in to record each of the 67 samples and we are now combining all this data into our Geographic Information System to create a chemical map of the data. Stay tuned for our results!

We are deeply grateful to Bruker for the loan of this instrument for our pilot study during the 2014 field school. If you have an interest in the Bruker Tracer III-SD pXRF instrument or learning about its other applications please visit the Bruker Elemental site at http://www.bruker.com/elemental or contact Bruker at email: e-info@bruker-elemental.net Phone:+1-509-783-9850

Sherlock Holmes meets Star Trek! Thank you for the great explanation Steven!

Star Trek indeed. Sounds like a ray gun. Looking forward to your results or conclusions!

This is the future….very exciting stuff, Steve.